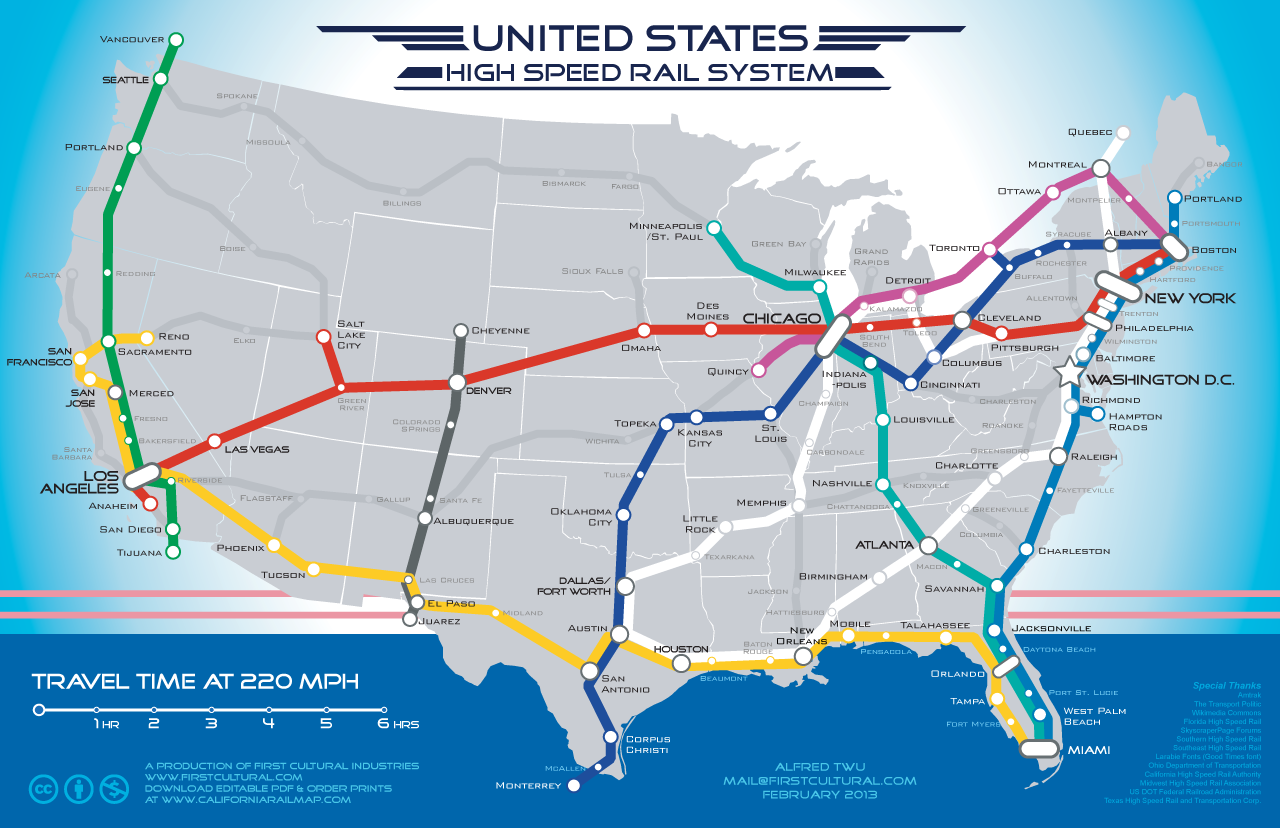

Map orientation shapes perception of the world around us

It’s pretty common to describe direction in relation to location on a map. Go up that way, down here, or over there. Up, down, and over are relative directions given from a point of reference, often physical topographic change. Up river, down the hill, and over to the lake. Sometimes though, place names become engrained in our cultural lexicon simply because of their location on the map. When is up ‘actually’ up? And when is up constructed by decision of the cartographer? How do decisions by cartographers shape our mental image of place?

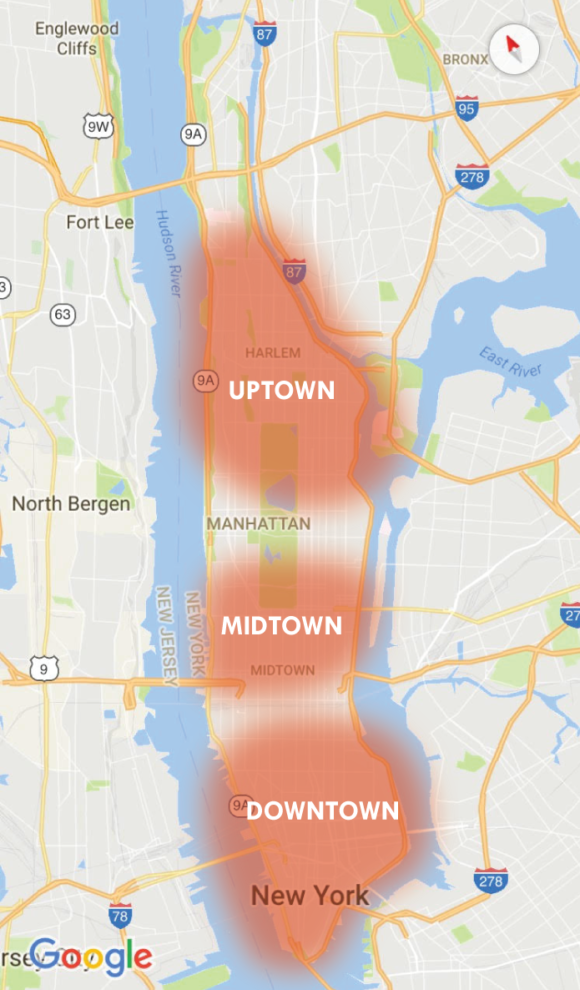

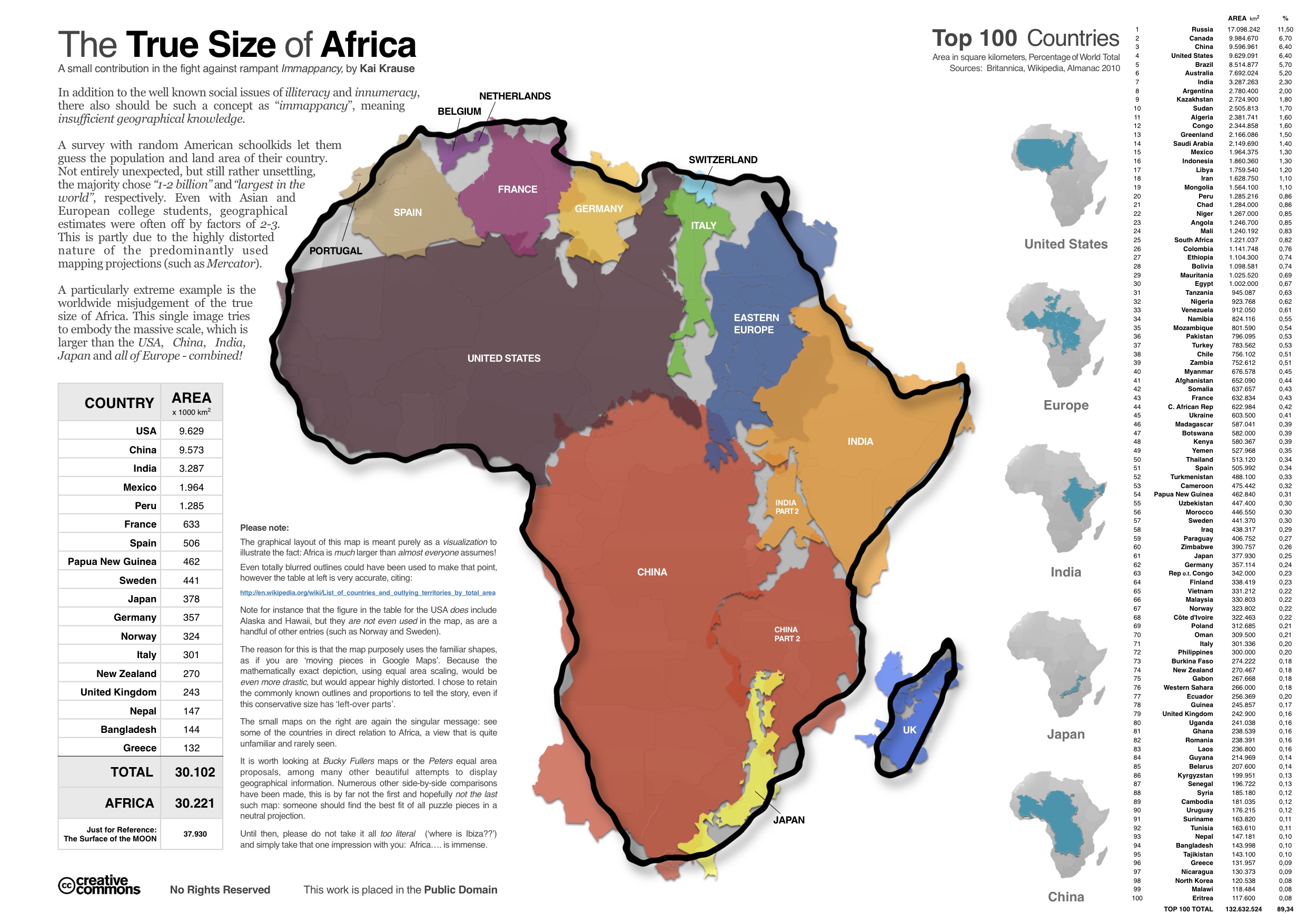

Modern cartographic standard almost always places north at the top of the page. This is not universally true, historic Middle Eastern maps placed east at the top, and cartographers aiming to combat a history of northern imperialism have ‘flipped’ the world map upside down since the 1930s. Considered though, to what effect has cartographic choice on relative directionality had on the establishment of local direction-centric lexicon? Where are local uses of relative direction (ie up or down) based on cartography, versus a geographic reason or topographic change? Looking around for examples, New York City actually covers both bases. Uptown in Manhattan is not only at the top of the map, its also ‘up the Hudson’, and downtown is at the bottom of the map.

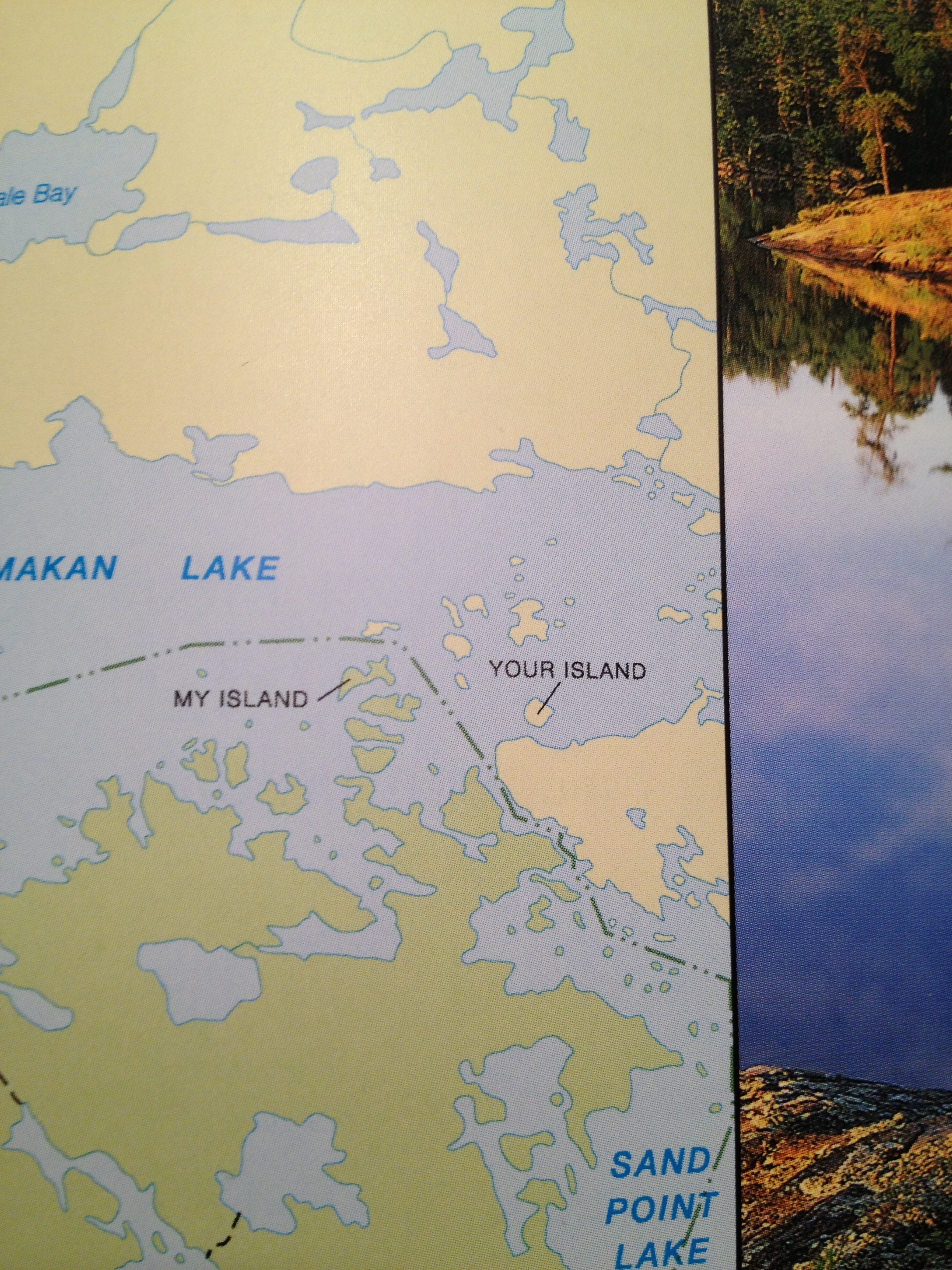

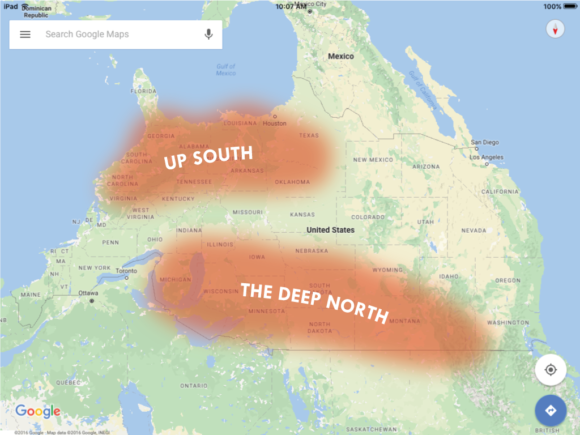

Maps construct reality as much as they are shaped by it. Over time, many regional lexicons have developed simply based on map orientation. For example, in the Upper Midwest, going “up north” means a getaway to the wilderness in the north. Looking ‘down south’, the ‘deep south’ might be considered deep only because it is so far from the top. One travels “over east” when traveling from the interior to the country to East Coast. Globes almost always place the north pole at the top, which is in theory, arbitrary, and most view the world through the distorted parlance of Mercator. Map orientation shapes our sense of the world and the places around us.

Where are uses of relative direction are actually based on cartography?

Which local references to direction (up or down) were actually created in relative reference to mapping and cartography, as opposed to geographic reason or topographic change? The answer is qualitative, fuzzy, and everywhere. The terms up and down can be held relative to gravity, but holding them reference to a scaled representation of earth actually doesn’t make much sense. Unless you are referring to up and down in relation to topography, or relative to a certain location (ie upstream refers to water coming from a higher elevation), up and down are meaningless terms unless the common representation of the place is in a certain spot on the map. Perhaps the most egregious misuse of these relative directions is the land ‘Down Under’, Australia, given this name due to is location at the bottom of the globe.

Map Orientation affects Perception and Recognition of Space

Say you were to ask a friend to draw the United States. What are the chances they put Florida at the top? Chances are, if Florida is at the top, they would simply say the map is wrong. Technically though, the map isn’t wrong at all… its just, different. It represents the same locations.

Map readers construct cognitive maps based on gained or learned geographic knowledge of the areas in which they live and operate. Mental maps of the United States almost always have the northern tier of states at the top. The maps are built around coastlines, major highways, and key points of interest. For example, look at the Greater Boston. Most have a vivid mental picture defined by shorelines and freeways. Route 128 circling the city to the left, downtown jutting out to the northeast in the center, and the harbor islands and beaches dominating the right side of the map.

Some cities flipped in a direction where north is not the top become immediately foreign, even though the map depicts the the exact same accuracy and resolution as any map with north at the top. Flipping south to the top challenges our mental image of the place and changes the paradigm in which we have built our internal navigation and recognition models. When this construction changes, a well known area can look like an entirely foreign location.

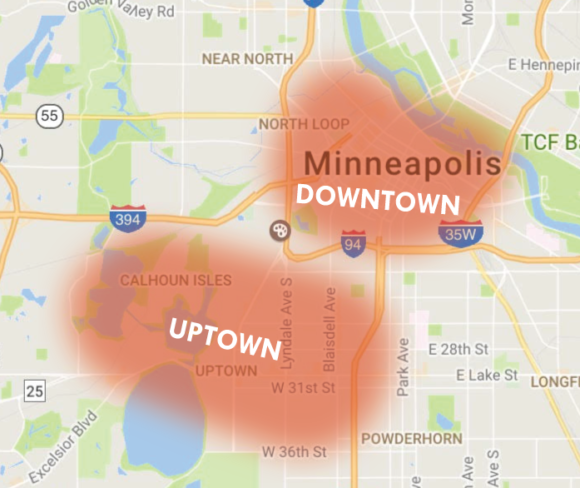

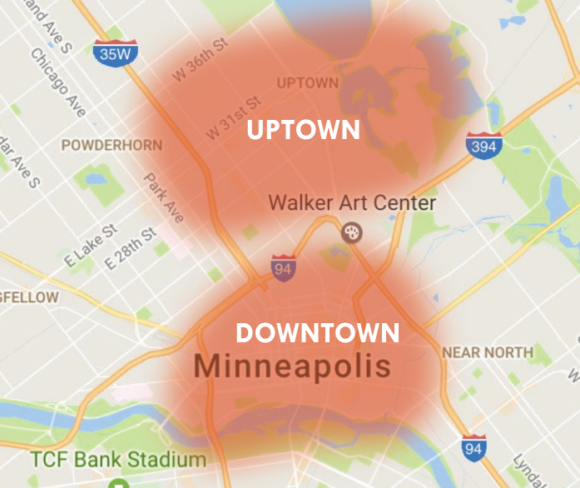

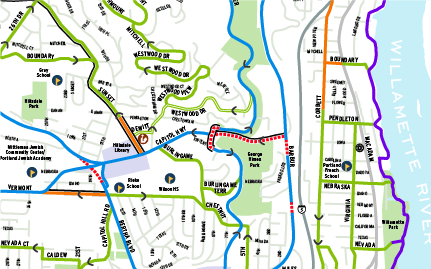

Digging around a bit, you find evidence of relative directionality all over the map, each begging a story that narrates why these places have been given these names. Take Uptown, a well known neighborhood in Minneapolis. Cartographically, why is ‘Uptown’ located below ‘Downtown’?

The roots can be found in the historical development of the city. Uptown, in this circumstance, is up and away from the Mississippi River. Many historical maps of Minneapolis use the Mississippi as a geographic foundation for the map, and anything moved away from the river is also ‘up’ the map.

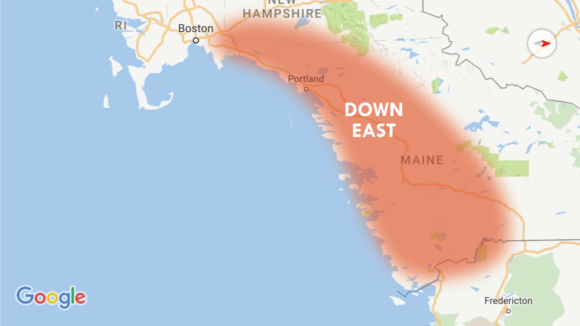

New England is a curious example. Traveling ‘downeast’ in New England actually takes you north! This was not based on map orientation, but rather on prevailing winds traveling from southwest to northeast. Historically, sailing ships going to the east would be sailing downwind from the settlements around the greater Boston area to get Maine and other points further north.

Cartographic decisions produce identity as much as they represent it, and locally relevant directional cognition has developed based on a cartographers decisions on what to put at the top of the map. It’s very simple to change map orientation, but over time, it can become foundational to a readers perception of space and how they perceive the world around them. Entire regions of our country, in part, can be traced to cartographic origins. Depicting those regions in any other way is technically accurate, and provides insight into how the people of the area have built their mental images of space into their greater culture.

This is a small sample, but there are many different locations around the world where position on the map has provided identity of place. There are probably some in your city, and you can probably find them on the map.

Why don’t we go “Up South”? Because somewhere a cartographer decided to put north at the top of the map.

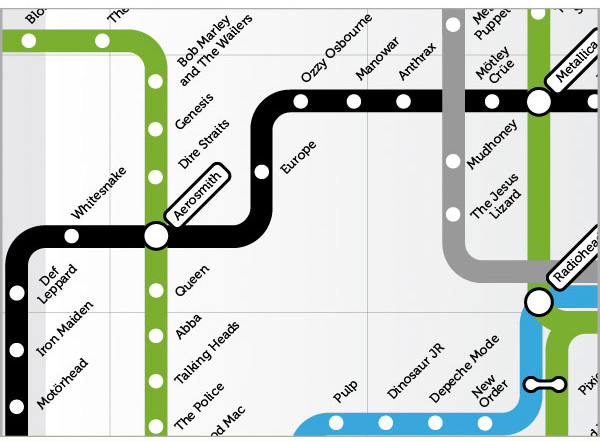

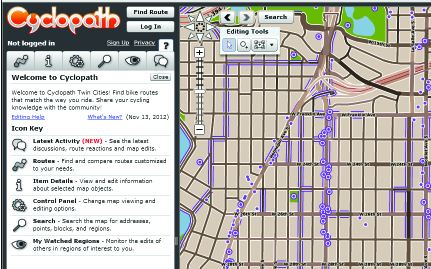

Cartographers have long had a quirky, and sometimes strange, fascination with transit maps. Since the days of

Cartographers have long had a quirky, and sometimes strange, fascination with transit maps. Since the days of